The Data Issue: School Improvement, College Success

The UChicago Consortium on School Research has been helping Chicago Public Schools use data to improve for decades. Director Elaine Allensworth's new book shows schools how to pick metrics that matter.

In her new book, Using Data to Improve Schools, Elaine Allensworth shows school leaders how to set their vision, cut through the noise, and focus on the metrics that matter. Board Rule talked with Allensworth about her new book and its lessons for school board members and central office staff, as well as for principals and school leadership teams. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Why do a book like this now?

A. We've been talking at the Consortium about wanting to support better use of data and metrics in schools. We've learned so much about school improvement and what really matters. People think the data tell them things it really can't tell them. They'll use the same metric for everything, and it just doesn't work. You have to make sure you're using metrics for the right purposes.

Q. What big idea do you want people to take away from the book?

A. I focus on the idea of leverage a lot. Is [a metric] predictive of the outcomes you're aiming for, and can you move it?

Schools could have many different kinds of big-picture goals. So you want to think about, what is the big vision? Then, what are the big things that are really predicitve of that vision that you can actually move? How much will change in this metric lead students to reach those bigger goals: graduating from high school, getting a college degree, having success in the workforce, having a love of learning, or civic participation?

That's the whole idea of leverage.

Q. Even though the era of No Child Left Behind is over, there's still a lot of pressure on schools to raise the percentage of students scoring proficient on standardized tests. You argue that other metrics may have more leverage toward achieving big-picture goals for students. Why?

A. This is one of those glaring cases where a metric that's good for one purpose is being used for purposes that make absolutely no sense. It will just frustrate people no end and provide a lot of false information to students, the public, and schools.

People think proficiency means grade level. It doesn't mean grade level; it just means whatever point [test companies] have set it at. Standardized tests are designed to spread students out as much as possible. This idea that we're going to get all students to the same level completely contradicts the design of the metric, which is trying to spread students apart. All the students could not be above average.

Standardized test scores are useful for understanding students' general skill levels in math and English language arts. The tests really do provide information on who is most likely to need extra help and who is ready for advanced work. But once you get past the early elementary grades, they barely change at all. We have a metric that grows very little and has a lot of imprecision relative to how much it changes. That fact that [scores] grow so little, especially in the middle and high school grades, suggests to me that they are not capturing most of what students are learning in school.

People think [a standardized test score is] predictive. It's somewhat predictive of how [students] do later. But there are so many other things that matter beyond their tested skills for how students do in their later years.

Q. So if improving the percentage of students proficient on standardized tests isn't the best starting point for school improvement, what are some good starting-point metrics for schools trying to improve?

A. People are discounting attendance all the time. They'll say, "Oh, we don't want just seat time." If you have goals around improving attendance and decreasing chronic absenteeism, and you really focus on supporting students who have between 85% and 95% attendance, those are students you could have a big effect on. Their attendance in school is highly malleable based on their experiences in school and the supports they get. And [their attendance] is highly predictive of their learning gains and their grades and their eventual educational attainment. So attendance is one that's predictive. It's highly malleable. It has high leverage.

Q. It seems like the primary audience for this book is principals and instructional teams. In Chicago, we have network chiefs, central office, and then board members, folks who are looking at school improvement from the 30,000-foot perspective. What do they need to know?

A. I did design this for principals and school leadership teams primarily, for sure, but I was thinking that it would also be useful for folks in the district or school board to have an understanding, so that they are providing the supports that schools need, and so their policymaking is consistent with best practices for schools.

If your policies are all focused on this vision of getting all students to proficiency on standardized tests, then schools are going to have to focus on that, even if it doesn’t make sense. And, even if the way to get more students to perform better on the standardized test is to focus on other metrics, schools aren’t going to do that.

The entire conversation was fascinating and would take up too much space for a single newsletter. Watch for a special holiday edition of the full interview, which you'll be able to read at leisure.

As a school district, Chicago Public Schools has made notable headway in moving two high-leverage metrics for high schools: freshman on-track and college enrollment. If you haven't read Emily Krone Phillips' outstanding book on how Chicago's public high schools made the shift from letting ninth-graders sink or swim to closely monitoring their performance, put The Make-or-Break Year on your reading list.

Now we'll look at the latest news on CPS college enrollment and persistence.

Moving a Metric: College Enrollment

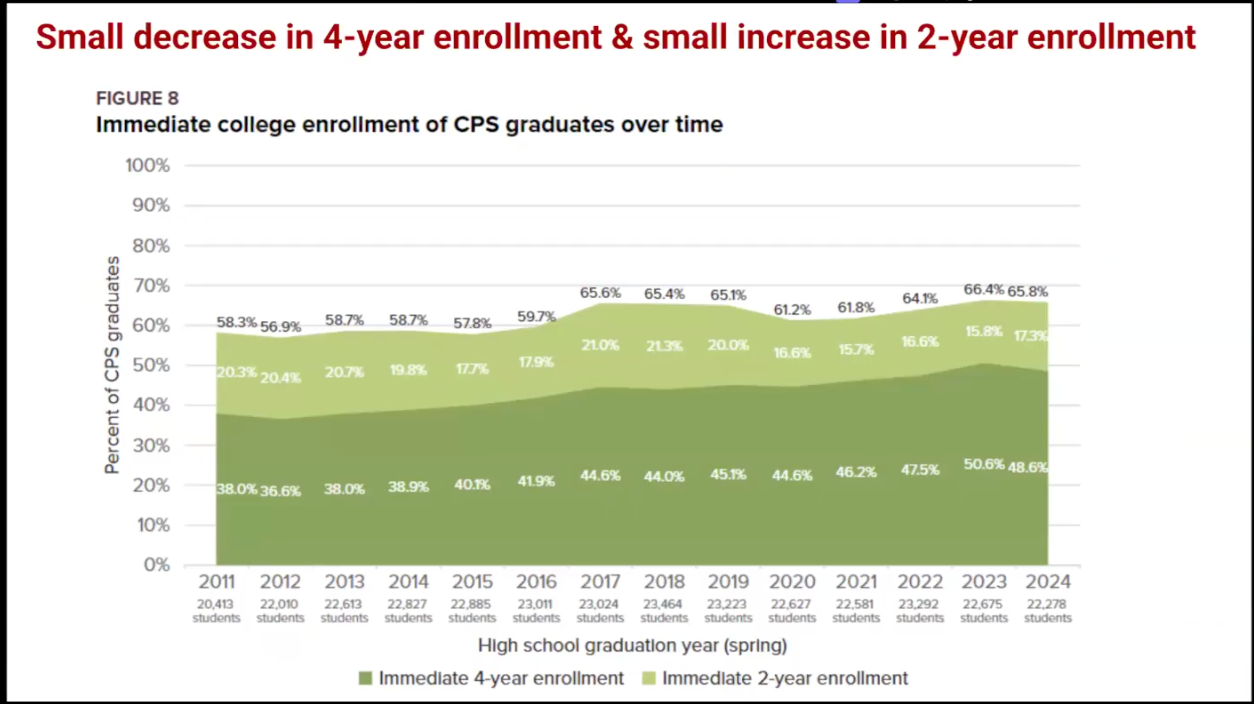

Last week, the Consortium released its annual report on the educational attainment of CPS students. The report focuses on college enrollment for the graduating class of 2024 and on college completion for the class of 2018, the most recent class for which there are six years' worth of data on college persistence and completion. The good news: 66% of 2024 graduates immediately enrolled in college, outpacing the nation. The not-so-good news: the share of 4-year college enrollment dropped slightly from 2023, and the share of 2-year college enrollment ticked up. Axios Chicago offers a solid summary of the report.

Jenny Nagaoka, deputy director of the Consortium and a co-author of the report, said the delayed rollout of the new FAFSA in fall 2023, which delayed financial aid awards, likely affected students' college choices, forcing some to change their plans away from 4-year programs to community college. "Anecdotally, it’s pretty clear that what happened with FAFSA did shift how students were able to make decisions about where to enroll."

At the same time, the school district's investment in postsecondary advising may have limited the damage. "CPS has been investing really, really heavily in school counseling and other supports to help with this process," Nagaoka said. "It’s entirely possible in the absence of this effort, we could have seen a much larger decline in 4-year college enrollment."

Chicago Public Schools' commitment to increasing college enrollment and even completion dates back to 2006, when the Consortium first examined bachelor's degree attainment for CPS graduates. Their findings shocked the city: only six of every 100 CPS ninth-graders were earning a 4-year college degree by their mid-20s. For Black and Latino boys, only three of every 100 were likely to earn a bachelor's degree.

Since that time, the school district has used a variety of policy and practice levers to push high schools to better support students as they prepare for life after graduation. Two of the best known are the Star Scholarship, offering free tuition to City Colleges for CPS graduates with a 3.0 or higher GPA, and the requirement that every graduate develop a postsecondary plan, known as Learn. Plan. Succeed. CPS, City Colleges, and the University of Illinois-Chicago are also building a pipeline known as the Chicago Roadmap to ease the often-rocky transfer from 2-year to 4-year college.

But several less prominent levers have also pushed the increases. The school accountability system (now in the midst of a revamp) included graduates' college persistence as a metric of high school performance. The district has encouraged– and paid for–high school counselors to earn certification as college counselors. Those counselors make sure high school seniors complete college applications and the FAFSA. Following the groundbreaking work of charter schools like North Lawndale College Prep, CPS now has alumni counselors checking in with graduates attending college to help them stay focused and troubleshoot academic and financial issues as they pop up.

"It's audacious, what they are doing," said Nagaoka. "Twenty years ago, at best, high schools only cared about making sure students graduated. They didn't have this sense of responsibility about what students did after high school."

But there is still more work to do, especially to ensure young Black men are well served as they prepare for life after high school. "Black young men are not graduating high school at the same rates as Black young women," said Nagaoka. High school graduation is the first big hurdle students must clear on the road to a college degree. "Black boys' experience in school is an area that needs a lot more research."

Hot Takes

New state laws create more protections for undocumented immigrants in early and higher education. Yesterday, Governor JB Pritzker signed a package of bills intended to strengthen protections for immigrants regardless of legal status, in Illinois' courts, hospitals, child care centers, and public colleges and universities. Chalkbeat's Samantha Smylie details the provisions in early and higher ed.

Not-So-Fun Fact: According to a new poll commissioned by Kids First Chicago, only one out of every three Chicagoans knows the school board will become a fully elected body in 2027. Only one in 10 city residents could name their current school board member, though the share of CPS parents who knew their board members was closer to two out of 10. WBEZ's Emmanuel Carrillo digs in.

Christmas Wish...Board Member Emails! Months ago, board member Therese Boyle mentioned that CPS would be publishing board members' official emails on the Chicago Board of Education website, with their bios. Still no sign of them...could Santa make it happen?

Comments ()