'Vexed' Choices: Cut, Borrow, or Win More $ From State, City

What to do about Chicago Public Schools' $734 million budget deficit? Parents say no borrowing. The Chicago Teachers Union says the state should pay more. No one wants cuts, but what else is left to do?

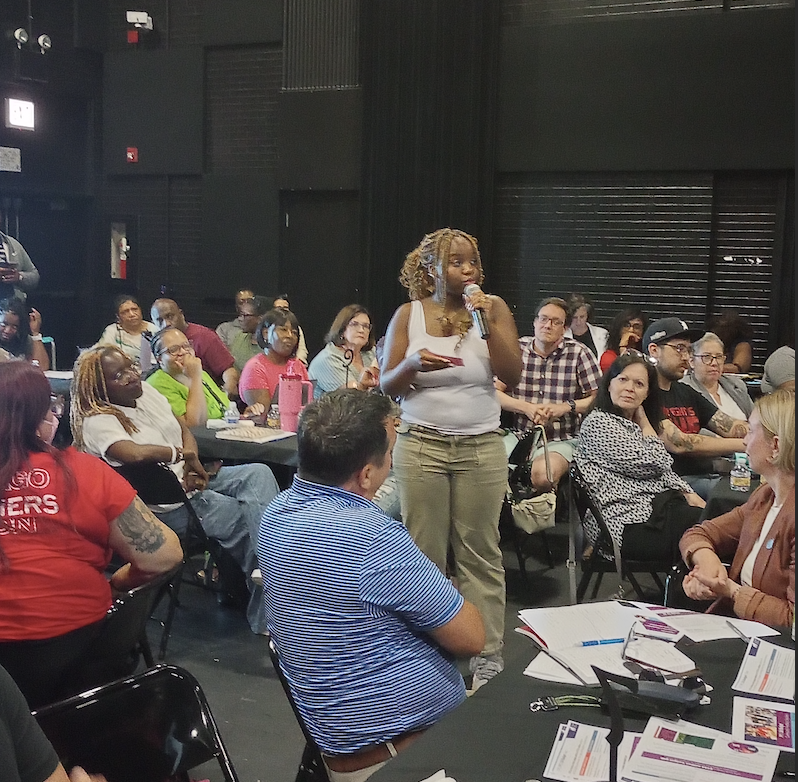

Over the last week, Chicago Public Schools hosted five public conversations where parents, teachers, principals, elected officials, and anyone interested in the school district's challenging budget situation could share their thoughts on what to prioritize and how to plug its $734 million budget hole. Most of the discussions followed a standard format: a presentation on finances from CPS budget director Mike Sitkowski, followed by table conversations answering a limited set of questions. Only at Westinghouse did folks challenge the format.

You can view the slides from Sitkowski's budget presentation in English or Spanish, or check out an hour-long video explaining how CPS got into this mess, here.

Across the city, the conversations I heard focused on three main buckets of ideas to plug the hole. Borrowing was discussed, but only the hardest-core Chicago Teachers Union members actively promoted it as a short-term solution. The most popular ideas by far were to win more money from the state and the city, combined as necessary with cuts as far from classrooms as possible. A handful of parents and community residents were willing to discuss consolidating schools, but only if CPS is prepared to tackle school consolidations thoughtfully, equitably, and with real attention to improving the school experience for all students involved. Many parents wanted to know how much CPS is spending on basic upkeep for closed school buildings, and what is being done to sell and repurpose them.

A clear message from all the meetings opposed cuts that would affect the student experience. Parents questioned why special education classroom assistants (SECAs) are being cut before cutting administrator positions in schools or central office. A national expert I spoke with (who asked not to be named because she was speaking without formal authorization from her employer) noted that Chicago, like many school districts, has already made deep cuts to its central office over the last two decades, and questioned how much was left to cut there.

CTU had a solid presence at all the discussions. At Dyett, I had the opportunity to ask a school-level union leader why CTU thinks pressing the governor and state lawmakers for a special session this summer to help CPS will work. According to this person, Gov. JB Pritzker is a good target because he appears to be preparing to run for president. He can't make a successful presidential bid if he has political trouble at home, the thinking goes, so if CTU, CPS, and school districts create enough political trouble for him, he'll find a way to find more money to keep his constituents back home happy (and his Democratic teacher union allies sending money, was not stated, but is a logical extension of the argument).

I asked him why push in Springfield first when Mayor Brandon Johnson has direct control over TIF funds. The CTU rep said he thought that would let Pritzker off the hook for delivering the state's long-awaited and long-promised fair share of school funding. But he acknowledged that TIF funds would have to be part of the solution.

At the Roosevelt High School budget discussion, Illinois State Senator Graciela Guzman promised to speak with the CPS department of intergovernmental affairs about how to push for a special session. This morning, WBEZ reported that board members Jitu Brown and Debby Pope are leading Chicago's push for a special session.

Unfortunately for this strategy, every local finance and politics expert I spoke with sees little chance of a special session this summer to help CPS. Though the legislature passed a balanced budget for FY 2026, it doesn't address the fiscal cliff coming to public transit when federal pandemic relief money runs out in early 2026. With big federal cuts to Medicaid coming Illinois' way, too, the state may have to adjust its budget, but schools won't be the top priority.

"Politically, I'm not sure that an emergency session is very realistic, at least for the CPS issue," said Elaine Gaberik, director of policy analysis at the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability. New state revenue, like taxing consumer services as well as goods, could be a possibility down the road, but new state taxes aren't likely to happen until next year at the earliest.

According to WBEZ, Board President Sean Harden sees borrowing as an option if the state does not come through this summer. "The impact of the cuts would far exceed the interest we would have to pay," he told reporter Sarah Karp.

But he also supports making the controversial $175 million payment to the city pension fund that supports retired non-teaching staff in CPS, as well as city workers. Eight board members' opposition prevented the school district from making that payment to the city this year, but it is back on the table for FY 2026.

Many parents at the community feedback sessions preferred to see the city pay that $175 million, as it is legally obligated to do and as was standard practice before 2020. Kids First Chicago is leading an organizing effort to oppose CPS making the payment in 2026.

Thinking Outside the Box

School district officials billed the sessions as an opportunity to hear from the public about the direction they should take as they look for solutions to balance the budget. But at Back of the Yards College Prep on Saturday, parents pushed back against this ask. During a table conversation, a Spanish-speaking parent argued that parents are always looking for more money for their schools, and holding conversations to ask parents how to fill a budget hole is inherently unfair. "CPS needs to realize they are the ones that need to find the funds. Why are they making us work for this? We work hard enough. This is not our burden to carry."

They also challenged the framing of special education as an extra cost to the system, as opposed to part of educating all students, which should be viewed as an ordinary cost. "Special education students shouldn't be seen as an [additional] expense. They are making it seem like our children with IEPs are a burden on the system. We need to focus on all our children," said the parent.

My favorite one-word summary of the problem came from a veteran teacher on the far South Side, who called it "vexed." It's a difficult problem that sparks anxiety and anger. This calls for outside-the-box ideas, so here are a few. Some ideas received less airtime during the community feedback sessions but warrant further discussion:

Merging the Chicago Teachers Pension Fund with the state's Teacher Retirement System, which could help lessen the burden on Chicago Public Schools. CTU opposes this idea, preferring to keep control of the Chicago teachers' pension fund.

Selling ads on school property and CPS-owned vehicles. This is controversial, but school districts around the nation have done it.

Raising the property tax extension cap (PTELL), so that Chicago Public Schools can increase how fast property taxes grow. Back in the Vallas and Duncan years, CPS didn't raise property taxes to the limit set by PTELL, but under Mayor Rahm Emanuel, when pension debt exploded, the district began to go to the maximum increase allowed each year, and will continue to do so for at least the next five. years. But it might be necessary to ask voters to allow a higher increase. The Forest Preserves of Cook County successfully made this kind of ask in 2022.

Allowing CPS to raise taxes through ballot referendums, like every other school district in the state.

Partnering with other branches of government, with City Colleges of Chicago, with youth-serving nonprofits, and with community organizations to maintain services and experiences for students despite the budget problems.

When cutting, ensure that schools where key positions have already gone unfilled for years (like math, science, and special ed teachers) get those key positions filled before they have to face cuts. Direct cuts first to local communities that have the resources to make up for a loss of district funds.

A parent asked: Can CPS take money out of the police budget and put it toward schools? Not directly, but if the city continues to expire TIFs, money will move away from city TIF funds, which are used for development projects, to the school district. This could eventually force adjustments to the city budget that would involved the police department, but that would be over years.

Here are more questions I've heard either during sessions or from parents directly.

How much is the Chicago Public Schools paying out annually in legal settlements? Are there patterns in these lawsuits--particular schools, networks, or CPS departments getting sued more frequently than others?

How much is Chicago Public Schools paying for outside legal counsel?

What can we do to eliminate waste, inefficiency and potential fraud among CPS vendors? Why does it cost five times as much to buy school supplies from Lakeshore Learning (a CPS vendor) than for a teacher to buy the same supplies at Wal-Mart?

How much has already been decided? We may find out more about that tomorrow, during the budget presentation at the July school board meeting. Here's the agenda. There will be an update on the FY 2026 budget after public participation and a recess (usually that's 30 minutes). There is no closed session on the agenda this month.

Comments ()